International Tea Day and Portugal’s Deeply-Steeped Love for the Ancient Drink

The sacred leaf that transformed global trade and Portuguese society is celebrated worldwide — and it continues to stimulate the communities of Lisbon and beyond discovers freelance journalist and strategic communications consultant Miles Bullock of Vivid Atlantic.

This week, the world pays homage to tea — the most consumed drink on the planet — behind only water. The tea tree or shrub, scientifically known as ‘Camellia Sinensis’ bears an aromatic leaf that is small in stature, but massive in global significance. This year, the United Nations designates the 21st of May with the theme of “Tea for Better Lives,” in recognition of the plant’s rich heritage and its ability to create positive economic and cultural impact. According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Office (FAO), the international tea market is valued annually at USD 9.2 billion and sustains more than 13 million people worldwide, the majority from smallholder tea producers, and it continues to expand.

As one of the world’s first truly global commodities, tea’s path to international sensation reflects more than just the emergence of large-scale trade but deep cultural diffusion. For Portugal, Europe’s sole industrial producer of tea, this journey reveals the vastness of its maritime history and the many cultural fusions that define its identity today.

Blended Roots of Agriculture and Philosophy

The origins of tea’s cultivation can be traced to Central Southeastern Asia, where the wet monsoon seasons regulated agricultural practices and fueled maritime trading networks in the region for over 7,000 years. Along the verdant slopes of southwestern China, these patterns led to the cultivation of tea nearly 5,000 years ago. It’s here, at the center of a powerful system of evaporation, condensation and precipitation — stirring earth and sea through thermal energy, where tea was first grown, revered and traded. “The climate, altitude, soil and rainfall create ideal conditions for tea plantations in Southeast Asia,” explains Marta Mundo, a ceremonial Japanese tea specialist and former scholar at Fundação Oriente.

According to Marta, the plant’s proliferation reflects far more than expanding agricultural production and consumption, but a transmission of spiritual values which lay at the heart of an exchange of eastern philosophies. “(Japanese) Zen Buddhism…has its roots in (Chinese) Taoism. Many Japanese monks came to China to learn a lot about Buddhism. For the monks to meditate for hours and hours, they used tea to stay awake during meditation,” she says. As these monks returned to Japan, they brought the tea seeds and the knowledge of cultivation that would eventually give birth to Sadō — or Teaism as it’s referred to in the West — a sacred ritual closely bound to Japanese Buddhist thought and a way of life. “It’s just serving tea, but it’s not just serving tea. Sadō is a do, like aikido, judo, karate-do, it’s a path.”

As tea and its infused philosophies began to spread across Asia and beyond, the only route west to Europe was long, land-based and perilous.

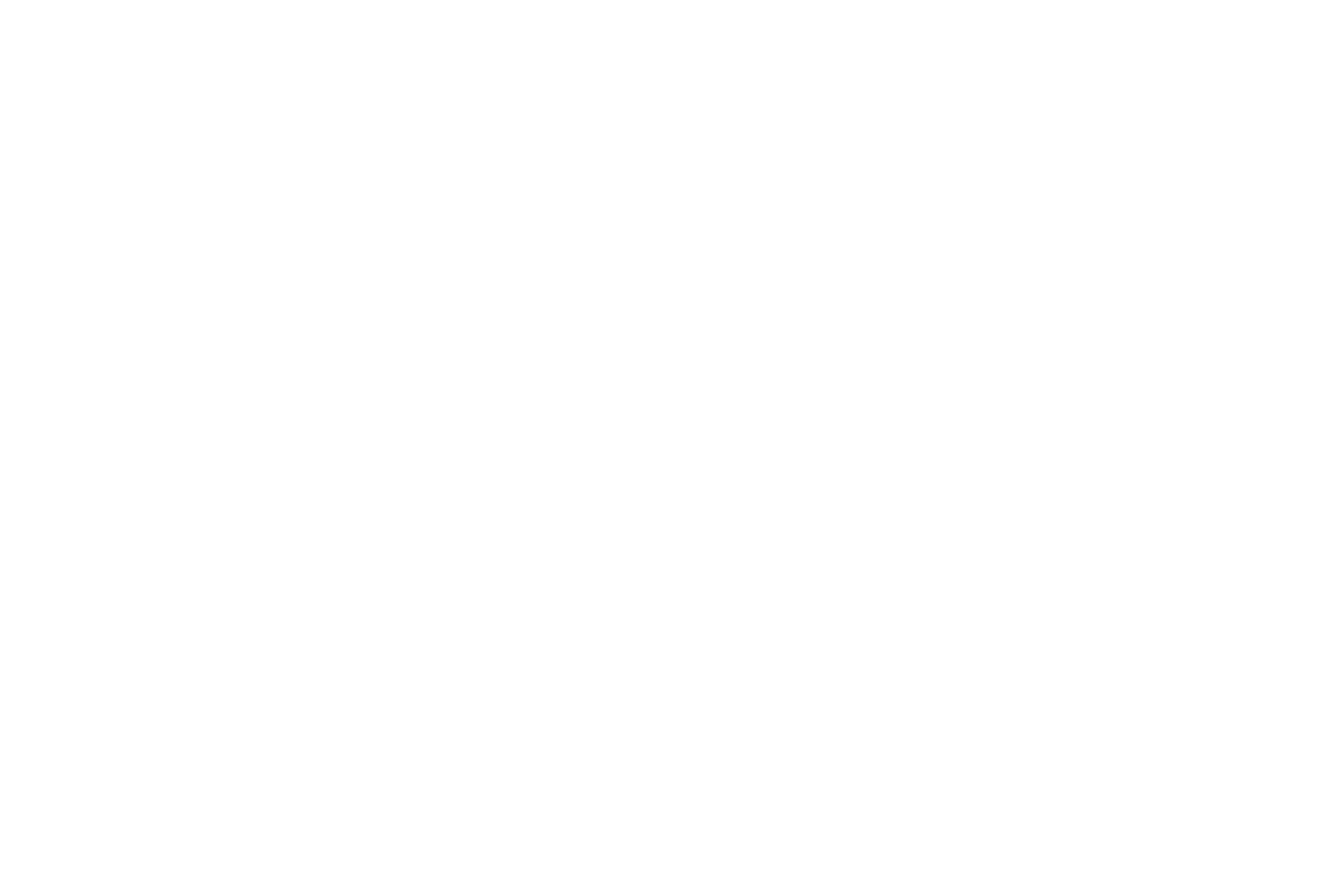

Below: A Chinese watercolor painting dated around the early 19th century illustrates tea cultivation in China. [Image provided by Fundação Oriente]

Portuguese Navigators Reach the Far East

Aboard their carracks and caravels, Portuguese explorers such as Vasco de Gama and Alfonso de Albuquerque set sail from Lisbon and rounded the arduous waters beyond the Cape of Good Hope where the Atlantic and Indian Oceans meet, eventually reaching India’s Malabar coast by 1498. It wasn’t long after when explorer Jorge Álvares, who along with Portuguese merchants and priests, finally made first contact with tea in China in 1513.

Chá, as it’s still referred to in Portuguese in keeping with the Cantonese origin word, quickly caught the attention of Western visitors in their newly reached world. The Portuguese Jesuit missionary Luís de Almeida would witness the Chanoyu — the Japanese tea ceremony — carried out by leading tea masters of the day in the palatial zashikis “gathering rooms” of the Imperial Kyoto Court and estates of Japanese warlords.

“The Japanese are very fond of an herb agreeable to the taste, which they call chia.” Luís de Almeida (1565) One of the first recorded accounts of tea by a European.

From Asian ports like Macau, tea would find its way back to Lisbon, arriving in Portuguese court where it would become a favorite drink of Catherine of Braganza, Europe’s most pivotal tea aficionada.

Below: A 17th century Nanban folding screen displayed at the Museu do Oriente depicts the arrival of the Portuguese in Japan in 1543. [Photo: Miles Bullock]

Tea Takes Root in Europe and Stirs Up Social Transformation

Long before becoming synonymous with British culture, tea beyond being a medicinal concoction was practically nonexistent in England and much of Western Europe. That all changed when Portuguese princess Catherine of Braganza was wed to King Charles II of England in 1662. The young queen was highly fond of imported tea, so much so that she brought chests of it with her to England’s royal palace where she consumed it regularly. The subject of both scrutiny and emulation, Catherine’s affinity for imported tea was soon copied by the British elite who learned to mimic the intricate tea ceremonies of the Far East. “The appeal of the Japanese tea ceremony for Westerners lies in the aesthetics and philosophy of the rituals. Western culture still sees it as exotic. The tea ceremony is part of a rich and distinctive culture (and) this contrasts with the mundane consumption of tea,” shares Marta who guides Japanese tea ceremonies across Portugal.

By the 18th century, England’s demand for tea reached a rolling boil. British importation through its East India Company more than quadrupled between 1720 and 1750 and would pass 6 million pounds (2,700,000 kg) by 1767. Price stability and accessibility secured via its Indian colonial holdings led to tea’s brimming popularity across Britain. Now served in both courts and local shops, tea became a part of everyday life for the aristocracy and the working class alike. During this period, mortality rates declined, as people were consuming boiled water and reducing exposure to deadly waterborne pathogens. The appearance of tea houses across Western Europe also went hand in hand with Salon culture, slowly blending the new drink with social norms that aligned with the Enlightenment ideals of the day.

A National Industry Emerges in the Atlantic

With demand firmly planted in Europe, the tea trade found a source of production closer to home — in the Portuguese Archipelago of the Azores, where the climactic conditions proved suitable for quality tea cultivation. In 1801, the very first crates of homegrown tea were shipped from the island of Terceira to the Portuguese mainland. Though it would be on São Miguel — the largest of the nine Azorean islands — where tea would be cultivated at scale.

Backed by the Sociedade Promotora de Agricultura Micaelense, tea became industrially produced in Portugal in the mid-19th century. In 1878, two Chinese masters from Macau, Lau-a-Pen and Lau-a-Teng visited the island to teach the trade to local growers. Their expertise guided the burgeoning sector and by the turn of the century, the Azores would be home to more than 10 factories and dozens of tea plantations, including the Gorreana Tea Factory, Europe’s oldest tea plantation which was founded in 1883. Over a century later, the fertile volcanic soil of São Miguel continues to support the specialized production of two types of Azorean tea — Green Tea and Black Tea, including its Orange Pekoe, Pekoe and Broken Leaf varieties.

“When I’m in São Miguel, I think I’m in Japan. It’s a little Japan in Europe.” Marta Mundo Ceremonial Japanese Tea Specialist.

Enduring Traditions and Establishments

Today, 1,400 km east of the Azores in Portugal’s capital, dotting Lisbon’s landscape, you’ll find a variety of shops that maintain the tradition of importing and selling high-quality teas. One such establishment is Lisbon’s Casa Marcário in the heart of Baixa Chiado, a centennial coffee and tea shop founded in 1913 which still busily operates today. “We have been selling Gorreana tea for 30 years. I sell almost as much tea from the Azores as all the others put together,” says Luís Torres Alves of Casa Marcário whose grandfather purchased the store in 1973, just before the Carnation Revolution.

Below: Luís Torres Alves pauses for a snapshot with Gorreana Azorean Black Tea (Broken Leaf) and Green Tea (Hysson) in between tending to locals and tourists at Casa Marcário. [Photo: Miles Bullock]

Azorean tea is popular among tourists, but it holds a special place for the Portuguese and continues to be important, as Luís affirms proudly, “it’s because it’s ours.” Over the decades, through Portugal’s economic and political twists and turns, Casa Marcário has imported coffee and tea from Africa, Asia and other distant regions. Today, Luís’ dwindling inventory reflects the previous year’s growing season in the Azores where he relays that, “the winter was very cold.” which caused yields to drop. “It always depends on the environment. At the end of May, beginning of June, there will be some.”

“In Portugal, it was said that a person from high society drank tea, played the piano, and spoke French.” Luís Torres Alves, Manager of Casa Marcário.

Looking back on over a century of business, Luís asserts that, “[tea] will be a popular drink because nowadays, besides tea, there are infusions…we make tea out of everything, you can make an infusion out of any herb. One for stomachaches, another for headaches, another to help you fall asleep, another to wake you up.”

Modern Blends for a Portuguese Way of Life

Nearby, in the buzzing neighborhood São Bento, Argentine Tea Master Sebastian Filgueiras is blending exotic, aromatic leaves at the vanguard of modern tea culture in Portugal. For Sebastian, tea is a timeless, noble product — and his shop Companhia Portugueza do Chá is a testament to his passion and the evergreen appeal of tea.

“In this shop we must have around 200 teas, I think. I never count them. Spring is coming, it’s just arrived. So all the fresh and new teas from the year 2025 are arriving. And spring is very important for tea, because it’s the first harvest, it’s the season of blossoming,” explains Filgueiras.

Below: The owner of Companhia Portugueza do Chá Sebastian Filgueiras holds a disc of imported Kunming Chinese White Tea. Harvested by hand, it is then stone pressed, aged and packaged, a tradition dating back to when tea would be stacked and carried along the terrestrial Silk Road.” . [Photo: Miles Bullock]

While some may think of espresso, port wine or jinjinha as Lisbon’s most iconic sips, tea may be the better reflection of Portugal’s unique outlook on life: mellow, calm and unrushed. In a market dominated by strong coffee, his hand-crafted blends continue to catch the attention of the community, including young consumers. “We have a lot of young people who come to buy tea…who are beginning to live tea…this Portuguese way of being, very calm, let’s make some tea…let’s stop for a while and then we’ll carry on. I think that this way of being, this Portuguese way of life and of getting through the day, leads to things going better and better results being achieved.”

Today’s Global Marketplace and Portugal’s Innovative Outlook

Increased productivity resulting from tea isn’t just reserved for the Portuguese. According to the FAO, the global tea industry has seen rapid growth over the past decades and is expected only to grow. Reaching a staggering USD 17 billion per year in production value, tea continues to find its way to customers’ cups worldwide, with 6.8 million tons produced in 2023 alone.

New market trends indicate that consumers are increasingly looking for ready-to-drink (RTD) flavored teas as they search for healthier alternatives to carbonated drinks. Over the last three decades, the industry has also seen a shift from “commoditization” to “premiumisation” of tea, driven in part by European demand and a younger generation seeking more fashionable options with organic health properties, notably green and black tea fusions, alongside RTD teas.

While climate change has alarmingly given rise to new European zones of cultivation, the Azores — where green and black teas are still cultivated with tradition and care — can continue to propel Portugal’s domestic industry. Regardless of market position, one thing remains certain: like tea, Portuguese culture is profoundly infused with the cultures and peoples which it touches, and as both a practice and a commodity, tea continues to influence the soul of Portugal.

“Tea is a drink that has traveled through different cultures, completely different from each other, but in each one it has adapted in a way…but always with the same message, which is that of welcome, of receiving…of hospitality.” Sebastian Filgueiras, Tea Master & Owner of Companhia Portugueza do Chá.

This week, as we celebrate tea and its ability to improve lives and support green economies, Sebastian’s words ring especially true:

“We will always need to have this connection with the land, with man, and with what defines us as human beings within an ecosystem and a planet. That’s what plants are for, the earth, the leaves, the water, and man in an almost meditative state, almost meditating, drinking.”

Miles Bullock is a US, Lisbon-based freelance writer and the owner of Vivid Atlantic.