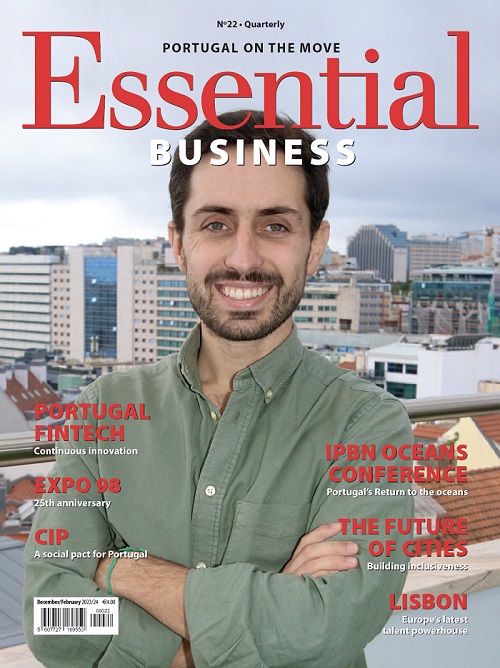

The man with the power to unlock genius

Portuguese émigré Alberto M. Carvalho left Lisbon at the age of 17 and emigrated to the United States with barely two red cents to rub together and a pocket full of dreams. Today, he represents the personification of the American Dream, a man who runs America’s fourth largest school district, Miami-Dade County Public Schools. How did he do it?

When Alberto M. Carvalho left his humble home in Lisbon’s Bairro Alto at the age of 17 to emigrate to the United States of America alone and almost penniless, his father, who had little more than a rudimentary education, gave him one piece of advice: “Son, wherever you are in the world, there you are.”

At the time, he didn’t understand what his father meant. “Wasn’t it obvious that wherever you are in the world that’s where you are?” he pondered.

Later on, after his father had passed, he would understand what his father meant… after a long journey from washing pots and pans and ferrying bricks to probably the most successful school administrator in the United States of America.

Today, Carvalho is one of the United States’ most successful educators and the superintendent of Miami-Dade County Public Schools in the south end of the Florida Peninsula. It is the fourth largest school district in America with 392 schools, over 346,000 students, 52,000 employees and an annual budget of US$7 billion.

The school district he is responsible for covers 2,000 square (3,218km) miles of diverse and vibrant communities, ranging from rural and the suburban to urban cities and municipalities – a truly global community of students that speak 56 different languages and represent 160 countries.

Carvalho, a recognised expert in educational transformation, modernisation and leadership development, has won more awards and accolades than he cares to remember.

In February 2014, the American Association of School Administrators (AASA) named him the 2014 National Superintendent of the Year and in February 2018 New York City Mayor, Bill de Blasio, offered to appoint Carvalho as the city’s next Department of Education Chancellor, a position he turned down.

Humble beginnings

But Carvalho wasn’t born with a silver spoon in his mouth. He had to earn it and fight his way to the top with sheer hard work, dedication and an unshakeable belief in himself.

He was born in Portugal to a father who worked as a custodian and a mother who was a seamstress. One of six children, he was the only one to graduate from high school and describes his childhood experience as one of “pretty dramatic poverty, living in a one-room apartment with no running water and no electricity”.

He arrived in the United States after leaving school in the early 1980s as an illegal immigrant and worked his way through university by washing up and working on building sites. He was even homeless for a time.

“My work has been deeply inspired by my roots here in Portugal; in the challenges I faced as a child, challenges that I saw my family facing and the families of many others. It is inspired by my experience as an immigrant in the US and the opportunities that I hope to realise for young people who may travel a similar journey,” Carvalho insists.

Referring to this experience as a “journey from the impossible to the inevitable”, Carvalho said it could only be travelled by those who exercise equal parts of belief, skills and will.

“I believe that all children have exactly the same number of chromosomes, an innate ability and a power and genius that must be unlocked,” he says.

“I have never met broken children, but I have met adults whose systems break their hopes, dreams and aspirations.I never blame the kid. In schools, you blame the adults who run them and pay attention to the parents who may or may not be a positive influence and guiding force for improving their child’s life,” he adds.

He admits that may sound harsh coming from him, but points out that his recipe has worked well in Miami and stresses that both belief and skill are important for knowledge; it is through the power of pedagogical skill that good teachers who have a passion for what they do can elevate children’s capabilities and can make or break their lives and their futures.

“Professionals have to have the right amount of determination, courage, passion and dedication for what they do. The most important element is having the will,” he says.

“How often does one want to do the right thing but lacks the political courage to take on the sacred cows and institutions to force gravity to work upside down?” he asks.

“It is necessary to overcome the gravitational pull of the status quo and that which seems impossible but seems so real in the lives of kids – that, in essence, is the recipe,” he explains.

Carvalho quoted Einstein by saying that sometimes the most vexing, complex problems faced have the simplest solutions and can be so obviously in front of our nose that we choose to ignore them.

Opportunity and access

As in the US, so it is in Portugal. Certain postal codes (ZIP codes in the US) in some of the richest cities are leaving children behind.

“How do we solve that? What my brothers and sisters lacked was not ability, intellect or intelligence; it was lack of opportunity and an equitable access to a high level of quality education. This continues to be among the combination of challenges that affect kids in Portugal and in the US today,” Carvalho explained.

“After living in this country for the best part of 16 years, I knew that by lacking power, resources or influence, I was not going to go to college. I had a decision to make and that first big decision in my life was to work hard enough to buy a ticket to the United States where I arrived in New York in 1982-1983. My first job was scrubbing pots and pans,” he recounted, adding that children sometimes confuse the label for the essence – “you don’t buy a candy bar for the wrapper but for the chocolate inside”.

“I was poor. I was an immigrant. I was unaccompanied. I was illegal. I had childhood epilepsy and, at one point, in great despair, I was even homeless in America, literally living on the street blocks away from where I work as superintendent,” he said.

“I truly believe I am unremarkable. If I made it, then every single kid in Portugal and America must make it as well.”

And make it he did! For the second year in a row, he was named Best Superintendent in the United States, as well as being a distinguished visiting lecturer at the Harvard Kennedy School. Carvalho was also honoured by President Barack Obama at a ceremony at the White House in 2014 with National Teacher of the Year and Principal of the Year awards.

Carvalho is the longest-serving superintendent of any large urban education system, in a school area where 75% of children come from families that are at or below the poverty level, where 80,000 students are foreign-born, where nearly 12% are handicapped, where traditionally there has been a great deal of violence, where, when he started, there was a deficit in the schools system of US$2 billion.

During his tenure, he not only paid off the deficit, but the graduation rate in the schools’ system had gone from 58% to 84%. The district has become the only major urban school system in America to have achieved an ‘A’ rating.

“Good education is not a choice, it is not a privilege, it is a right! Particularly in the richest country on earth where today we still deal with issues such as inequity, lack of access to education and quality health, food and security.

“I have used that discontent and source of disappointment as the fuel and energy for the reform I hope to see in our schools’ system,” he explained.

A father’s powerful advice

Carvalho concludes by telling a short personal story. “My father, José Maria Carvalho, had a third-grade education but was a brilliant renaissance man that played music, could play the guitar, sing and write poetry. Well read, he had had a very limited formal education. The last day I saw him before I went to the US, it would be five years before I would see him again. When I came back, I had a college education,” he recalls.

“No matter where you go, your dignity, morals, values and principles don’t change. You are the person you are despite the education, the possessions and title you may accumulate. Dignity matters. Who you are as a person matters. That advice from my father was the strongest and most powerful advice that I ever got,” he says.

At the American Club of Lisbon on March 25, where Alberto M. Carvalho as guest speaker received a standing ovation, ACL Club President Patrick Siegler-Lathrop reflected that he was a subject of admiration for the “example that he presents of an exceptional, outstanding and incredible life”.