How the resurgence of nationalism is shaping cybersecurity and the data economy

The challenges posed by cyberespionage, cybersecurity and information and technology theft are core concerns for western governments and corporations alike say cybersecurity experts António Gameiro Marques and Tim Maurer.

Text and Photos: Chris Graeme

Hacking data bases to steal confidential or highly sensitive information is a challenge not only for Western and European governments but also for major international companies driving some of the greatest technological innovations of our time.

With the old bi-polar order of the Soviet Union and United States swept away, the world has fragmented into a number of geopolitical spheres dominated by often politically volatile and or nationalist, highly armed centralised autocratic powers.

At the American Club of Lisbon this month cybersecurity in cyberspace was debated by two giants in their field: Tim Maurer, co-director of the Cyber Policy Initiative and fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a renown expert on cybersecurity, tech policy and geopolitics in the digital age and António Gameiro Marques, the General-Director of the Portuguese Office for National Security.

China, America and 5G

The strategic question now being discussed by American foreign policy experts is the potential decoupling of the economic partnership between the West and China which has been simmering since 2013 when a US Department of Justice Investigation uncovered evidence that Chinese agents sought to direct fund contributions from foreign sources to the Democratic National Committee (DNC) before the 1996 presidential campaign.

In 2014, Chinese hackers hacked the computer system of the Office of Personal Management resulting in the theft of 22 million personnel records handled by the office while in October 2018 the Senate Homeland and Governmental Affairs Committee held a hearing on the threat to the US posed by China after China allegedly embedded technology into microchips sent to the US that collected data from US consumers.

The most famous corporate case of all was in 2013 with Yahoo’s data breach compromised 3 billion people. The company revealed in 2017 that the accounts of every single customer at that time had been breached, including Tumblr and Flickr – just three of the major cases that have hit the headlines over the eight years.

Tim Maurer, acclaimed author of ‘Cyber Mercenaries – The State, Hackers and Power’ explains that during the Cold War when the “clash of systems” clearly took place at an economic and political level, the two were clearly separated and the West had institutions like CoCom (Coordination Committee for Multilateral Export Controls) which were designed to clearly control the export of strategic technologies and the Theory of Change was that that would ultimately lead to changes in the Soviet Union.

“The Theory of Change for China over the last 20 years has been very different, pursued by the US government. The Theory of Change was that increased integration was going to lead to a change over time, with the deliberate strategy of integrating China into the World Trade Organisation, integrating and reminding it of its responsibility in respect of the United Nations was a clear example that the Theory of Change was non-partisan in that sense, that China would reform from within. The change we have seen over the past few years across both parties is a serious rethinking of that relationship, with the possibility of China no longer being a cooperative partner with the US, but a competitor” says Maurer.

The tech sphere discussion has been dominated by 5G and Huawei. In the first year of the Trump administration there was a lot of continuity on how the White House thought about Cybersecurity. The one area where there was a clear difference between previous administrations was the focus on 5G as a transformative technology, and the US subsequently focusing and making it a priority, working with its allies and partners in Europe to make the case that Huawei, a Chinese company, should “not be part of that infrastructure, either in the US or in allied and partner nations”.

This is the first test case for the broader strategic discussion that started to bubble up in Washington about a potential “decoupling of the two systems” after a strategy of cooperation pursued over two decades.

“We would not be having this discussion on decoupling if all the energy over the past decades had gone into i ntegrating China into the global economic system and now the discussion is going in the opposite direction”, says Maurer.

ntegrating China into the global economic system and now the discussion is going in the opposite direction”, says Maurer.

Some multinational tech companies are operating on the assumption that some form of decoupling is going to take place in the coming years. They have been starting to think about the implications for their supply train integrity: should they leave the Chinese market and absorb the losses, or remain in what may be one of their largest markets. Microsoft, for example, chose to stay and created a China specific version of Windows.

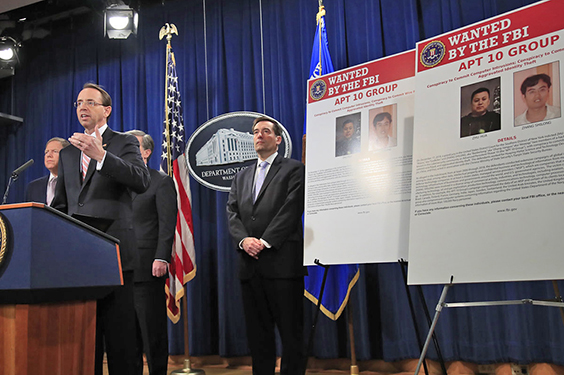

Maurer says that one reason why Washington has become so focused on China is concerns over intellectual property theft. During the Obama administration there was a very deliberate strategy to raise awareness that the Chinese government was stealing a lot of intellectual property, not just from US companies and the government but also from European companies.

There were indictments in which five members of the Chinese military were accused by the US Department of Justice of hacking US companies and stealing intellectual property and trade secrets. The threat of sanctions led to an agreement between President Obama and President Xi in which the Chinese agreed that the theft of intellectual property was “inappropriate”.

“It is the one example where people in government and in the technology industry both agree and it actually led to a decrease in hacking for between 18 to 24 months”, says Maurer.

“Hacking started to increase again in 2017 which is why so many on both sides of the House have significantly shifted on how they view China in recent years”, he adds.

This is part of a broader geopolitical battle over Data governance. After Edward Snowdon there were discussions about data localisation and the amount of mistrust vis-vis US companies over Europe calling for data to be held in Europe.

Snowdon is not only the case. India requires its data to be located in India. Brazil has had similar discussions.

“Decoupling and restricting data access is not just happening because of Russia and China. It is also happening in liberal democracies which after a few years have realised that certain countries are not aligned with the Western vision of an open, interdependent world order, but rather one where each country is trying to reassert its soverignty”, Maurer says.

“With Russia, China and some of the more authoritarian regimes we are clearly moving more into a world like pre-World War II, one of national governments and a focus on national territories and this is going to shape the data economy and the economy of the future because everything is becoming digital”, he explains.

In today’s multi-polar world, with different regions with different data localisation requirements, the initial vision of the founding fathers of the Internet of an open, transnational, anti-governmental network designed to avoid government control is being severely tested and questioned.

European dimension

In 2017, the EU Commission President Jean-Paul Juncker announced the Cybersecurity Act, a fundamental piece of legislation that outlined the framework for Cybersecurity as far as the EU is concerned in the wake of the establishment of the Network and Information Systems Security Directive 2016 that Portugal adapted and made law in 2018.

This law establishes the framework for all EU countries to guarantee that the Act in all Member States is followed and ensures they have the minimum requirements for its operation in a coherent and unified way.

“One of the key things that the Act establishes and which relates to 5G is that the EU will have a process by which all internet connectable equipment, be it hardware or software, must be certified so that the citizens that live within the European Union will know the usage of a specific device and how reliable and resistant to cyberattacks it is” says Gameiro Marques. The framework was discussed in Brussels in September 2019. The question is how does this relate to 5G?

“Regarding 5G, I think the EU and Member State governments woke up too late. However, there were companies that through a consortium were able to deliver a 5G solution. 5G is not just a telecommunications infrastructure, it is a technological revolution.

“It will be so embedded in our lives that people will no longer need a local air network in their homes or organisations because 5G is so detailed and capable of connecting the devices in an office with each other (Internet of Things)”, explains Gameiro.

5G has increased both bandwidth and velocity so that a lot of computing power can be put on the edge of the network (i.e., close to consumers) and companies will be able to develop devices to take advantage of that.

Because of the granularity that 5G brings to our lives, it also increases the thread surface, and given the fact that the thread surface has increased so much, so too have the cybersecurity risks.

“Each EU nation has been developing a global 5G risk assessment since July and in Portugal we are completing ours, developed by the Portuguese regulator ANACOM which will be delivered to the Government and intelligence services in September 2019”, he said.

The national security director left some words of warning: “There is a myth that cybersecurity is a technological issue and a lot of high-ranking people in this country and others think that if they have a good IT team, one that is very knowledgable about security, then they will have everything taken care of. This is very dangerous because it concerns society as a whole.”