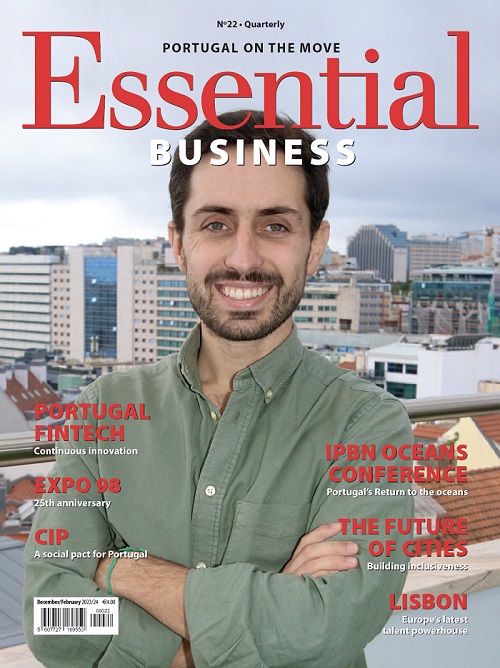

The Day After: Can the PS government use its election majority to really change Portugal?

Portugal’s Prime Minister António Costa and his ruling Partido Socialista party won a clear majority in Portugal’s General Election at the end of January. As the dust settles, five leading lights in Portuguese business, economics, and academia assess the results, and point to the course the government now needs to take to improve the economy and provide favourable conditions for companies and investment.

Text: Chris Graeme Photos: AmCham

António Costa is Portugal’s prime minister for a second term, having won an outright election victory without the need to form a coalition with other political parties in the Portuguese Parliament.

This gives him a golden opportunity to carry out a raft of reforms to the public administration, the legal system, tax and the overall modernisation of Portugal’s business network to make its companies more agile and able to compete in the international export market. But these reforms risk slaughtering sacred cows on the side of a social contact that has been in place to a greater or lesser extent since 1974.

However, while Portugal is on track for GDP growth at 5% this year, in the words of António Martins da Costa, President of AmCham Portugal (The American Chamber of Commerce in Portugal) which organised the event ‘The Day After the Elections’ in February, there is the responsibility of allocating some €16Bn of EU RRP funding, considerable uncertainty internationally with creeping inflation, high energy prices, supply chain problems, the continuing hangover from the Covid-19 pandemic, and geopolitical tensions over the future of the Ukraine and Taiwan. The sands are shifting.

The Present of the Portuguese Industrial Association (CIP), António Saraiva ,admitted the election results surprised everyone, including the prime minister, the question is what would the government do with the political stability of a parliamentary majority? While accepting the recovery would be slow and uneven as costs rise and external factors beyond Portugal’s control, there were challenges at home still to be faced, including social, demographic and productivity problems.

“The Government now has the responsibility to begin the reforms that this country needs. We are being overtaken by EU Member-States in Eastern Europe and yet the band keeps on playing while the Titanic sinks”, he said.

“The country’s policies have to be well-structured and the county has to look at its resources, including the economy of the sea and our forests, all of which need to be exploited and developed”.

“If we can design an agreement of the kind I have been calling for (both in parliament and with social partners), we will have the right conditions and sustainability to begin these tax and legal reforms, and a proper reform and streamlining of the public administration”, he added.

Lack of long term vision

Economist Vítor Bento, Chairman of Portuguese Banking Association, who highlighted the various challenges Portugal faces including regulation, governance, mechanisms of risk compliance, inflation and interest rate hikes, spending choices over the RRP and investing EE funds Portugal 2030, as well as fintech and cryptocurrencies, said: “in Portugal we have a deep-rooted problem and while we don’t overcome it we will have difficulty in sorting out our problems. Yes, we’ll crawl along, but not really thrive, and that main issue is that we don’t think, we’re better at action than thought”.

“We’re more adept at short-term measures than thinking long term. We don’t think systematically and systemically, which are essential because the social reality is made up of complex systems, and we take a decision to achieve a specific effect, forgetting all of the other indirect knock-on effects that this action causes as a chain reaction in the system, very often resulting in a result that wasn’t the one desired”, said the economist, adding that no one during the election campaign seemed to have “any better ideas than raising salaries”.

Are Portugal’s social rights sustainable?

António Lobo Xavier, lawyer, politician and consultant for national and international companies, was more optimistic. He said António Costa was “pragmatic, practical and adaptable”and had succeeded in getting an absolute majority after two elections without one, which had never happened in Portugal.

“The result was not a surprise; the surprise is that politicians don’t know who they are speaking for because the bulk of the Portuguese in the public administration only worry about balanced state accounts when the country is faced with bankruptcy and their pensions and salaries might not be paid.”

“The far right spooked people by saying the devil was coming, but the devil didn’t come, rather an angel arrived which was the European Central Bank (which because of the bazooka) meant that not having national accounts balanced wasn’t such a problem after all”.

Lobo Xavier said it was difficult to explain to the ordinary man in the street that in the medium term the size of the public administration, the pensions, and minimum salaries could not be sustainable, and these social rights might not last forever.

“People vote for the present, for their immediate happiness, there’s no point telling them they have to tighten their belts and cut spending, but the lack of consideration for sustainability will undermine the actual rights of this electorate that thinks these rights will last forever”.

Risk and opportunities

Pedro Duarte, President of the CIP Strategic Council for the Digital Economy and executive at Microsoft Portugal, pointed to three risks and three opportunities that had emerged from the elections.

The first risk was a “Mexicanisation” of the political system, meaning that one party or bloc turns into the only power alternative, as was the case in Mexico with the Institutional Revolutionary Party for six decades, which isn’t a “healthy situation” for an evolved democracy” he said pointing to the Socialists governing Portugal for 24 out of the past 30 years.

A second risk was for those in power to feel a certain “self-sufficiency”, particularly after an absolute majority, reducing their ability to be open to listening to others and compromise. The third risk was the “automatic conviction that the policies pursued by the government over the past four years, must be the right ones”, because, after all, the PS party won the general election with a majority, when in fact the Government had been helped by external factors overseas it had nothing to do with.

As to opportunities, Pedro Duarte said that there needed to be a “refocus” of government that was no longer dependent on the PCP Communist Party or Left Bloc, and the reality (which is unique in Western democracies not including two-party systems), in which two central parties have a 70% control of parliament which was a “huge advantage”.

However, the rise of the far-right, whilst worrying, would not, in his opinion, be a growing trend and had probably “reached its maximum peak”.

Last, Duarte says there are now the “ideal conditions for reform in both the medium and long terms thanks to political stability” which will also be helped by EU funds and an overseas context which is still favourable.

Lack of risk-taking culture

Isabel Gil, Dean of Lisbon’s Universidade Católica, pointed out the “stability and predictability of the status quo” that António Costa’s reelection would undoubtedly bring for the next four years, and confirmed the electorate’s aversion to in taking risks. She said it reflected the general lack of education in creativity and appetite for risk in Portugal that made the United Sates higher eduction system stand out.

“Taking risks is something that isn’t done in terms of projects to develop our social model which was very evident in the election results. “We continue to be a country of grants, subsidies, and dependent (irrespective of the political party) for decades on a structure which is a reflection of our difficulties” meaning the country’s ability to stand on its own two feet independently, without the public entities of the nanny state.

“It remains to be seen if with this majority government, and with the reforms mentioned which Portugal desperately needs, it decides to opt to intervene in crucial areas to do with our economic performance and reforming justice which is absolutely a priority, and with the cooperation of the opposition PSD party”.

So, things are looking up for the Government which has a golden opportunity to reform the State, its public administration, its slow and ineffective legal system, to modernise its companies and get them productive and exporting if it can work with the main opposition party.

But, as CIP’s António Saraiva warns, without the support in parliament of the far left parties, the new government is likely to face more demonstrations in the street and strikes. “I think social conflict will get worse”.

Panel Photo AmCham: L-R: André Veríssimo – Moderator, António Saraiva – CIP, Isabel Capeloa Gil (Universidade Católica), Vítor Bento (Portuguese Banking Association), António Lobo Xavier (Business Consultant) and Pedro Duarte (Microsoft).

Family Photo: André Veríssimo, António Saraiva, António Martins da Costa, Isabel Capaloa Gil, Vítor Bento, António Lobo Xavier and Pedro Duarte.