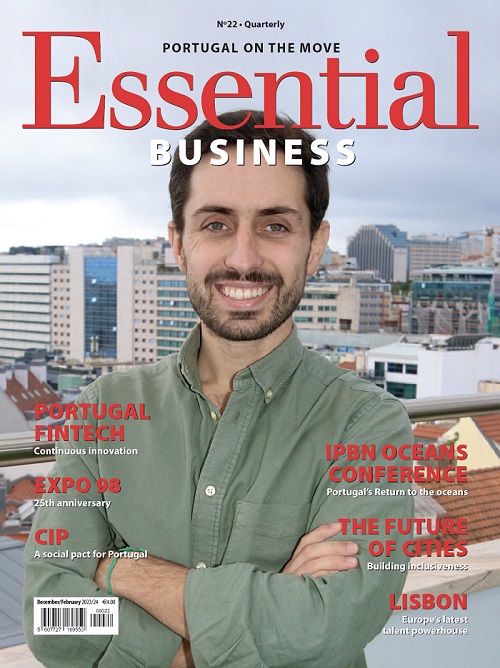

How Portugal’s trade and investment agency helped change Portugal’s perception overseas

Changing perceptions about Portuguese talent, creating value added propositions, and encouraging export-focused companies has been decisive in attracting Direct Foreign Investment to Portugal and boosting sales overseas, Luís Filipe de Castro Henriques, President and CEO of Portugal’s overseas trade and investment bureau AICEP tells the American Club of Lisbon.

Text: Chris Graeme

Moderator: Stephan Morais (Indico Capital Partners)

Photos: Joaquim Morgado

How did you reach the position of leading AICEP?

I grew up in Brussels and moved back to Portugal aged 19. I studied economics at the Catholic university. I first worked for the US consultancy McKinsey, working in America before moving to the Ministry of Public Works and then the Ministry of the Economy, specialising in Foreign Direct Investment which later became important as a background for my future role as CEO of AICEP.

Returning to academia and studying for my PhD at Cambridge University I had a ‘Eureka!’ moment and realised I didn’t want to work in academia. I completed by masters in Economics, did my MBA at Insead. I then the joined the energy company EDP for 5 years before joining AICEP as the CFO.

How did you start at AICEP?

When I started, my job was to drum up Direct Foreign Investment. I’ll never forget my first briefing. Unemployment at the time was 17% and so the Vice-Prime Minister Paulo Portas said: “Just do anything to generate jobs in Portugal”.

“I’ll never forget my first week in London to drum up investment after joining AICEP at the end of the Troika period (2014). The person I was talking to had the Financial Times in front of him and the second story on the page was ‘Portugal runs into trouble again’. I thought: “What am I doing here? There’s no possible conversation to be had!”. But we turned the situation around, and when the AICEP CEO Miguel Frasquilho left to manage airline TAP I became president of the agency because of the successful work I was doing for investment, and I have been doing that for the past 5 years.

Why did you go into public service?

When I worked at the Ministry of Economy in 2004-5 I clearly remember when investors began abandoning Portugal. The Keidanren (Japanese Business Federation) spent a week in Portugal to analyse how we were doing before leaving for Poland. They wrote a report which they shared with us. They predicted in 2004 what was going to happen in Portugal to 2012. It said Portugal was “going in the wrong direction”, it will be “highly indebted”, and “face competition from Eastern Europe”. For a German, British, or French company it didn’t “make sense to invest in Portugal with the fiscal imbalance that it has”.

To see this from the top decision-makers in Japan was sobering, so I wanted to do something to help turn the situation around. I was also sponsored through my higher education by Portuguese institutions like Caixa Geral de Depósitos, Gulbenkian or the Portuguese Government and wanted to give something back.

What does AICEP do and how big is the organisation?

AICEP is the Portuguese Trade and Investment Agency which means we foster exports from Portuguese companies or any company based in Portugal. It can be an American company and we’ll support you in reaching out to certain markets and segments.We are also responsible for inbound productive investment that generates jobs, as well as for large-scale national private projects of over €25 million that create jobs. In these cases we can provide grants, tax benefits, sorting out licensing issues, finding the right location for the company, factory or IT/R&D centre.

We employ 510 and have 50 offices around the world. We are in Lisbon and Porto (two-thirds of our staff), the other third is spread around 50 locations worldwide with delegations all around Europe, some locations in Asia: China, Korea, India and Malaysia. In the Gulf we have an office in the Emirates, Portuguese-speaking Africa, South Africa, Morocco and Algeria. In the US (New York, San Francisco and a new office in Chicago) and Canada. In South America we have delegations in Brazil, Mexico, Chile and Colombia.

What have you done to make AICEP a more efficient organisation?

The great challenges when I arrived as CFO and later as CEO was to make AICEP a more client-focused organisation. AICEP has dozens of demands from several stakeholders daily which are not from companies doing business abroad or investors from other countries. So we decided to focus on the companies which ultimately reflect in our key performance indicators. The first day I arrived I asked to see the Business Development Team. Everyone stared at me and thought “who the hell are those guys!” It turned out there were just two girls in the commercial team that drummed up new business. So, we created an actual Business Development Team and organised the commercial team differently to serve different segments of customers and exporters.

We were concerned about not overspending and we never did, but ultimately we only ever spent 30% of what we had planned, so we were definitely not doing our job. We changed that and gave more freedom to the delegations and now they help us execute our plans by between 88%-96%. Before, the delegations had always said they didn’t have enough budget. I told them that if they came up with a good project, we’d pay. By the second year we had big impact campaigns rather than small events and it worked.

When I joined the agency the average age was 50-52 years old. We have recruited a lot of younger people who have changed some of our procedures such as analysing with big data, studying markets in different ways, and some of our big delegations have 30-35 year-olds as directors.

Did you apply your private sector experience to AICEP?

We changed the mindset at the agency to achieve different and better results. My management experience and training and economics background helped me a lot. At the first board meeting I joined as CFO, the then CEO Miguel Frasquilho defined the new strategic plan whereby we would be opening 13 delegations in one year. The reaction from the management committee was “13!!We never open more than two in any one year!”. We did it and this kind of mindset showed us that we could change and we did.

How have you been fostering US-Portugal bilateral trade and investment?

On trade, the perception when I started working with the US was that Portugal was a good producer of cheap products with a certain amount of quality. However, we weren’t recognised in terms of quality versus price. The focus in the past had been quality and trying to upsell our products. We were able to do that in the textile, furniture and some machinery sectors. We had not exported that much to the US and that has changed now. The last campaign ‘Made in Portugal Naturally’ had a huge impact. It focused on furniture and home textiles that have a sustainable and natural component. It reached 2.5 million people in the US, mainly purchasers, and we have been seeing positive results from that campaign in terms of exports with products that are more expensive, increasing sales systematically every year. This was based on quality, design and some innovation.

Regarding investment, the approach was a development from one devised in 2015. The problem these days is that it is very difficult to sell a country unless you are a large country like the US, China, France or Germany, because people naturally have a notion of what they are, even if it is not altogether really true. When you are a country like Portugal, you are small, with several good attributes, and we are in the top 30-35 best countries to do business with in the world.

Portugal has top infrastructure in terms of transport, telecommunications and even research centres. But these things are not enough to differentiate your country. Why would investors come here instead of Ireland, Poland, Slovakia or Belgium? The feedback we systematically got back from our big clients was the impressive thing about Portugal is its talent. They said we were very well trained, speak several languages and this was different. These strengths were seldom mentioned in our presentations on Portugal. So we changed our emphasis to showcase our talent. For example, Portugal is the third country in Europe that has the highest output of engineers in terms of proportion of population.

When you start passing this kind of message, it has three positive impacts. First, it changes perceptions. A lot of people have a historical notion of Portugal – of sailing ships and discoveries.

When I went to meet customers in Tokyo in my early years at AICEP, the big Japanese investors had this idea that we were the same people who had arrived on sailing ships 500 years ago. We really needed to fight this perception. When we presented this talent approach, they started looking at us differently. They started to see we were well trained, we competed with the best universities in Europe, and that we were open to doing business around the world – which is not a feature seen in many countries – and on top that they were surprised that we wanted to deal with Japanese people who they themselves admit are culturally complicated. We do and we have had many successful outcomes. Things like this raise the bar in terms of the country’s perception.

Third, leveraging these factors to ensure, whether investing in industry or services, your productivity is higher than just the base service or base product. If you have talented people, even though you are hiring them at competitive prices, the differentiating factor is that they can all to do higher value added tasks. These were the three factors that really changed the perceptions of our customers. (24.12)

Photo: L-R: Stephan Morais (ACL Board member), Luís Filipe de Castro Henriques (AICEP) and Patrick Siegler-Lathrop (ACL President).